5 Ways Writers Can Prep for 2025 Goal Setting

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Revision is a chore every writer must tackle, but few truly master. Most of us can pick up a piece we felt we’d finished and find more to tweak, cut, or improve. Like our learning of the craft, revision is something ongoing.

Let’s look at some revision tools and techniques you may not have considered. Most of these things are created to help writers during the writing process, but they can be astonishingly helpful during the revision step as well.

“Many writers find that creating a story timeline helps keep their plots clear, their character arcs solid, and their narrative structures strong.” – Anusha M. Shashidhar

I’m presently in the middle of revisions for a middle grade novel. I have the editorial notes, and they also sent me a timeline they’d created as a tool for revision. I have friends who regularly make timelines, but I’d never really done that. But having one in front of me was interesting. The timeline for the novel was organized by chapter, but a timeline could also be created that is organized by plot chunks: scenes and skims.

You see every book I’ve ever written and many (if not most) of my short stories are built of scenes and skims. A skim is a transition between scenes where time passes, and I simply tell the reader what happened. For example:

“For most of the day, Drew paced the house, wandering from pointless task to pointless task, but always waiting for the phone to ring and everything good in his life to end. When the phone finally rang, he froze with his shaking hand hovering above a rather sickly philodendron. He’d been picking off the yellow leaves, trying to make it look healthier than it really was. The pile of curled, pale yellow leaves on the table made one fact plain. He wasn’t doing a good job as a plant parent. He was a failure.

When he finally forced his hand to move, it picked up the phone, and he croaked, ‘Hello.’ What he wanted to say was ‘Please,’ but he knew there was no way to talk the person on the other end into saying anything good.”

In a scene/skim-based timeline, you can use color-coding to note the difference or you can use labels or changes of font. I might insert this into a timeline synopsis of the chapter in this way:

[Skim] Drew waits for the call from the hospital by tending to houseplants. [Scene] After learning his father has died, he acts out by destroying the very plants he’d been trying to save. He only stops when his sister arrives and he tells her about their father’s death.

If I didn’t want to use labels, I might simply render the skim part in a different colored font.

The value of a timeline is that it gives you a sharply condensed overview of the work of the novel. We see how the character progresses along the plot journey. And we may see places where actions seem pointless or out of order. A timeline gives us a kind of distance, a way of looking at the shape of the plot overall, and that can show problems we didn’t realize we had. It can also point to important emotional markers in the story—important things you’ll want to mention when you need to write the synopsis that you’ll use to sell the finished piece.

“Style sheets help me to keep track of decisions and spot any problems.” – Louise Harnby

Timelines aren’t the only valuable tool I’ve met lately. Another is the style sheet. Now, I tend to outline my stories before I write them, and during the outline, I’ll list things like character names, age, time of year, setting, and note when the day or time changes. As a result, my outline can work as a style sheet. But I know many people don’t outline before writing.

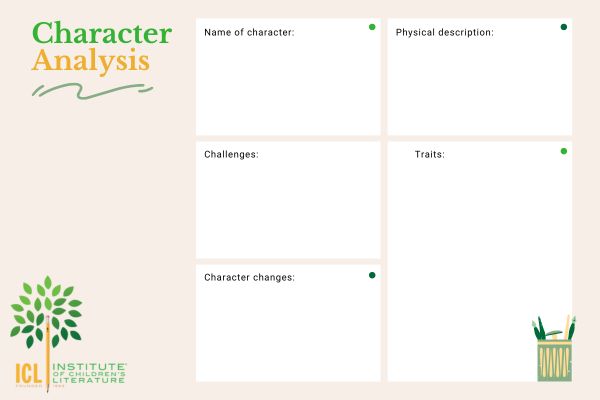

This is especially prone to happening with minor characters who come into the piece only now and then. I’ve talked about keeping track of these kinds of details in a “Series Bible” when you intend for a story to expand to many books, but these are details that are important to keep track of in a one-off story as well. And a style sheet is a great place to do this.

A style sheet will list the name of every character and the choice you’ve made as to how to spell that name. It will tell the character’s age and may include other details that you need to get right every time the character appears such as eye color, hair color, build, address, catchphrase, accent, injuries, etc. Then when it comes time to revise the story or the novel, you have a sheet that has all the decisions you made about the character. When you’re revising, you can simply check the style sheet to ensure what is on the page coincides with the specs in the style sheet.

“…A vision board stands as an encapsulation of the themes you’re pursuing.” – Hollie Jones

For highly visual writers, vision boards can be fantastic during the planning and writing process. They can be collection points for floorplans for the buildings you’ll use in the story, maps of the area, photo inspiration for characters, photo (or drawing) inspiration for character clothes. They can also include tiny scraps of text that come to you at odd moments when you simply “hear” exactly what these characters would say. Catchphrases, monologues, and sometimes little blurbs where you imagine how a character would talk about another character can all appear on vision boards.

This is especially true when you want to check the details of what you originally intended against what you actually wrote. For instance, in the book I’m presently revising, one of the characters is mourning the loss of a family member, and not handling it well. Because I knew she was mourning, I tended to think of her as sad. But I also knew what she was doing. She was arguing, judging, shouting, stomping, and generally being difficult. One of the things I had to do in revision was stop having my main character think of her as “the sad girl” because she wouldn’t have looked at all sad to him. They’re both kids. He’s going to think of her as the “angry girl” far more than the “sad girl,” and that’s likely to be true even after he learns about her dead sister. He’s going to judge by what he sees, not what I (as author) know. It was an error on my part and had to be corrected in revision.

If I’d had a vision board rather than a simple style sheet, I could have drawn lines between the characters and typified their relationships. The lines from the grieving girl to everyone else could all have been typified as furious. And when I saw that visually, I’d have been a lot less likely to make the mistake of having a character think of her as the sad girl. She is sad, in that she’s grieving, but she’s also really, really angry. Vision boards give us a visual system of understanding our character relationships and that can be hugely helpful in making sure what ended up on the page reflects what was really going on with the characters.

“Nothing is able to send me down into the depths of my story faster than music.” – Jillian Karger

In revision, a playlist is a good way to see if the emotional arc of the story that you felt in the music is coming out in the story. Are there discordant emotional notes in the story? Are there places where the emotions on the page don’t make sense with the sense you had of the person in the story. They’re also a great way to see if you made use of tools like setting and pacing to convey the emotional mood of the story. On top of that, some authors share the playlist they created to go with the book online and some even put them in the backmatter of the book. This adds an extra gift to the readers.

Timelines, Style Sheets, Vision Boards and Playlists are all tools writer can use throughout the process of creation. They can inspire creativity, help you overcome blocks, and bring vision and joy to the process, but they can also help you to see if what you wanted to create is what made it to the page. So don’t forget these unique tools during the revision process. They have a lot to offer.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Writers can be thin-skinned when it comes to getting feedback on their work. Let’s look at 4 ways to positively deal with constructive criticism!

Rejection is part of the territory when it comes to being a writer. Today we offer reflection for writers to help redirect your efforts after a rejection.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.