5 Ways Writers Can Prep for 2025 Goal Setting

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Many people equate book revision with grammar, spelling, and punctuation. In fact, some writers considering self-publishing for the first time don’t look beyond grammar, spelling, and punctuation in their revisions at all, always to their own detriment. Fixing these kinds of technical errors is important, of course. Readers are often tripped up by multiple errors of that sort and prevented from properly engaging with your work. Loads of small, technical errors can pull an editor or an agent out of a manuscript and give them a reason to reject the piece and move on to the next submission.

These elements are important, but they are part of the technical revision. Big picture revision is different. The primary purpose of a big picture revision is to make sure your writing, whether fiction or nonfiction, engages the reader at the beginning, keeps the reader through the middle, and offers a satisfying ending while leaving the reader with something to think about, something that lingers. This month, we’ll look at elements of big picture revision, beginning with the spot where you either grab a reader or push them away: the beginning.

The opening pages of your book, short story, or article are some of the most important you’ll write. Readers need some reason to commit to the task of reading on, and a poor opening is a killer. Readers have so many things competing for their attention in today’s world, so a book really cannot afford to be too much of a slow burn. This is true of work for adults, but it’s even more vital when talking about writing for children and teens. They need a reason to commit, and you need to provide it. A strong opening is equally important in fiction and nonfiction. The biggest task of the opening is the same in both: it engages the reader and makes the reader keep reading. But how openings work is different between fiction, narrative nonfiction, and informational nonfiction. Let’s begin with fiction.

What does your fiction opening need to have in order to engage? In Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, Jessica Brody talks about necessary elements of Act 1 structure. Though these elements are a movie construct (where they are called “beats”), they are found in the most compelling book openings as well. These opening elements will be found in those first pages. Here we’re going to talk about two of them: opening image and catalyst.

The catalyst is the bringer of change. All kinds of things can be a catalyst: a new baby, an unwanted move, meeting someone completely new. Again, quoting Brody, “something happens to the hero to send their life in a totally new direction.” This will be something active that leaves the main character with no choice but to act, to do something new. A good catalyst forces change. If the main character could ignore the catalyst without consequence, it’s not going to work to give you a story opening. A good catalyst is equally as important in a picture book plot as it is in a short story or novel plot. Consider Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendek. The main character is a wild little boy named Max who we meet making mischief, which is normal for Max. But this time, Max pushes his mother too far, and she sends him to his room without any supper. This is different. This is not what Max expects. He is now stuck, chock full of energy for mischief with nowhere to put it, so Max imagines an adventure that sends him to a place just perfect for a little boy to do his mischief without consequence. In this picture book, the catalyst quite literally pushes Max into a totally new world. Many times the push of the catalyst is a bit less dramatic, but it will always push the main character into something new and readers will eagerly follow to see exactly where this push takes them.

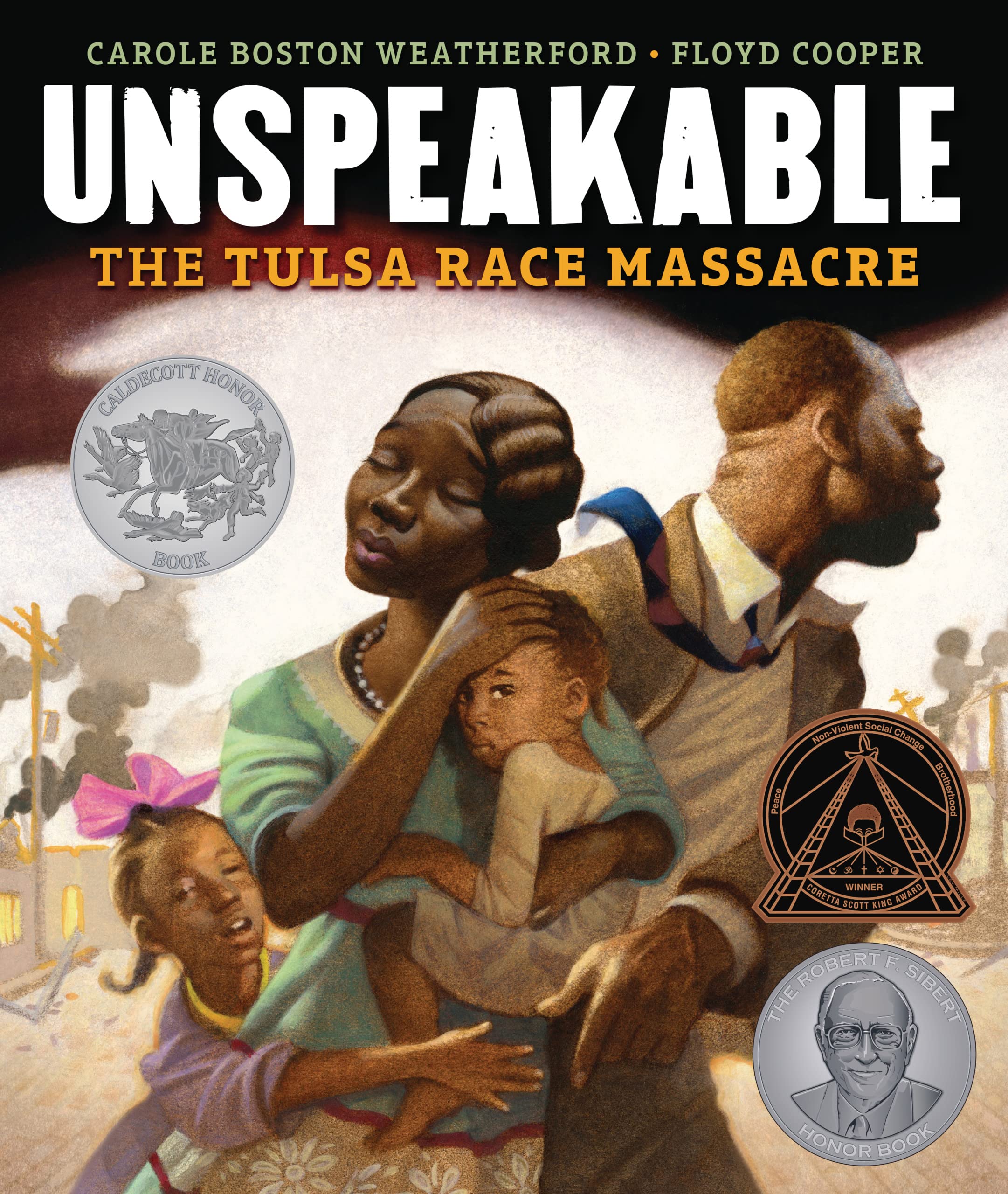

Narrative Nonfiction openings often have to do two things. They pull the reader into a story, much as a fiction opening does, but they also prepare the reader for the fact that this story is true. Let’s consider how this works with the award-winning picture book Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper. In this narrative nonfiction picture book, the author begins with a very “fairy tale” choice of wording: “Once upon a time near Tulsa, Oklahoma, prospectors struck it rich in the oil fields. The wealth created jobs, raised buildings, and attracted newcomers from far and wide, seeking fortune and a fresh start.”

This opening catches the reader both with the fairy tale element (which suggests we’re going to hear a story, not a recitation of facts) and with adventurous phrases such as “prospectors struck it rich” and “seeking fortune.” It sounds like a story that will have lots of action and things happening. At the same time, we also tell the reader that this happens in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which is very much a real-world location.

This kind of opening combines a story-telling feel with crisp facts about the time and the people. This opening engages. It’s hard not to want to read on, and that’s what you’re looking for with a narrative nonfiction opening. It is both a story and a factual retelling. Marrying both elements can be tricky, but it results in a story that readers simply cannot put down.

Expository nonfiction isn’t trying to tell a story (though sometimes it can contain small narrative moments within it, usually as examples). Expository nonfiction is designed to feed children’s thirst for information. In these books and articles, the point is to grab the reader with exciting facts while also letting us know the scope and focus that the book or article will offer.

In the expository nonfiction book Car Science: An Under-the-Hood, Behind-the-Dash Look at How Cars Work, by Richard Hammond, the opening page focuses on how knowing about cars is science. The first lines of the book press that point: “Cars are crammed full of science. How fast they go, how quickly they can stop, and how furiously they can go around a corner are all down to science.” The hook of this first line is that the way science works with cars is lively and exciting, and the writer intends to prove that to the reader. Notice how the author uses active, engaging words like “crammed” and “furiously” to make the opening even more exciting for the young reader. He goes on to use examples and analogies to keep the reader engaged while the car science begins to unfold. Examples and analogies are elements that make complex concepts easier to understand and keep readers connected to learn more. The first paragraphs make it very plain that the scope of the book is exactly what the title promises: it will show how the way cars are built comes from understanding the science in play when the cars are driven. It does so with strong verbs, engaging examples, and lively analogies—all valuable tools in making the opening engaging.

Consider the demands of your opening pages and even your opening lines in your fiction, your narrative nonfiction, and your expository nonfiction as you revise. Keep in mind that you don’t have much time to grab the reader and convince him or her to come along with you on this reading adventure. Now examine your own openings. Do they do what they should? And if not, what will you do about it?

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Writers can be thin-skinned when it comes to getting feedback on their work. Let’s look at 4 ways to positively deal with constructive criticism!

Rejection is part of the territory when it comes to being a writer. Today we offer reflection for writers to help redirect your efforts after a rejection.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

6 Comments