The Layers of Revision

To many, writing is revision, and most writers revise their manuscripts numerous times before they’ve shaped it into the best version that it can be.

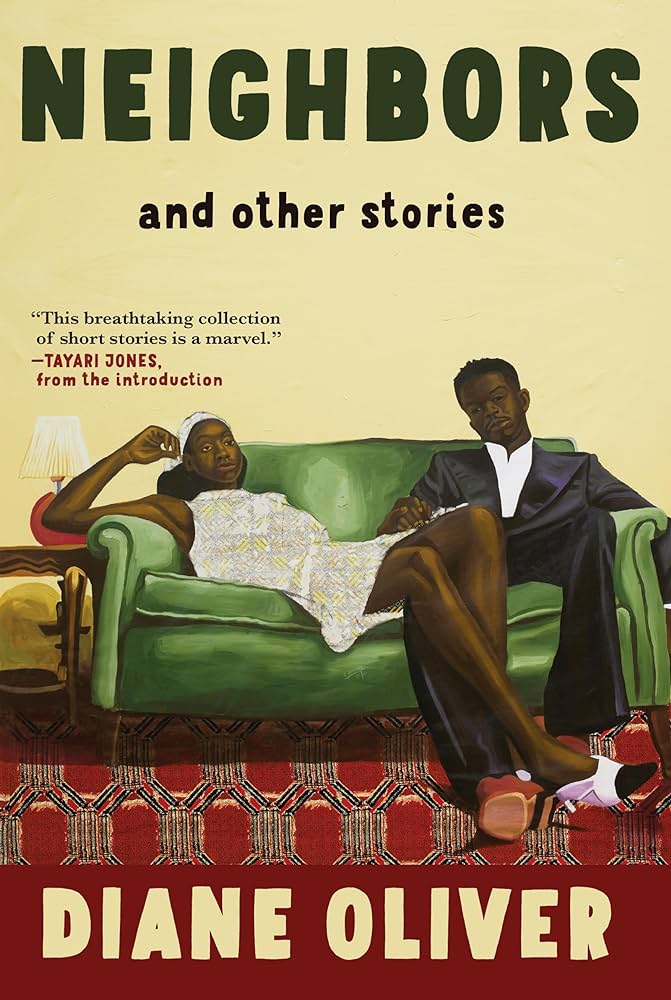

I recently learned about the writer Diane Oliver, who was a student at the Iowa Writers Workshop in the mid-1960s and one of only two African American students studying there at that time. Her stay at the university was short—Ms. Oliver died at 22 years of age of injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident while living in Iowa City.

Although her writing was not well known at the time of her death, Ms. Oliver did have early success by seeing two of her short stories published, and this was most likely the reason she was admitted to the elite writing program.

Although her writing was not well known at the time of her death, Ms. Oliver did have early success by seeing two of her short stories published, and this was most likely the reason she was admitted to the elite writing program.

Decades after her death and at the urging of a family friend in the publishing industry, Diane’s sister unearthed her old notebooks. The stories within them were exceptional and ended up recently published as a short story collection. Neighbors and Other Stories (©2024, Grove Press) is a notable compilation of stories with a distinct voice. Ms. Oliver set her stories in the middle of the 20th century during the time of the Jim Crow era and she highlighted the racial discrimination and segregation prevalent during that period.

What was most remarkable to me as I read Neighbors and Other Stories was the writer’s voice. Diane Oliver had a gentle, almost matter-of-fact way of writing. Her words were smooth, her characters all had unique and interesting personalities, her sentences were tight and her narration was subtle. This was all, I now realize, the unmistakable voice of this gifted writer.

This authenticity was present in every story in the book. I could probably identify a Diane Oliver story now just by reading a few pages.

Most of us have a favorite author or two, or maybe a half dozen of them. When we read a book by Colleen Hoover, Edith Wharton, or Ernest Hemingway, for example, we can usually tell that it is written by that particular writer. Some writers create descriptions of places or scenes that could take over a page of text (Herman Melville comes to mind) and others use just a line or two to set up that part of the plot. Reread a particularly gory scene written by Stephen King and realize that it would be tough for another author to affect our emotions in exactly the same way.

Your Voice is Uniquely You

Your Voice is Uniquely YouA writer’s voice has a unique and specific makeup and among other components, voice is a melding of word choice, writing style, tone, and a writer’s perspective on the topic they are writing about. Differences in writing styles are what makes us love certain writers.

Each of these short paragraphs says the same thing. Read them slowly and pay attention to the words, style, and structure of each:

Version 1: Gina Richards, MD, had nowhere to go on Friday afternoon, so she stayed home and watched a movie on television. About halfway through the movie, the power went out.

Version 2: Busy Doctor Gina found herself happily alone and unscheduled that Friday afternoon. She was excited to stay home and take to the comfy couch in her den, television remote in hand. It only took a moment to settle in with an old classic Julia Roberts movie. Gina was content until halfway through the movie when the power went out.

Version 3: Ah, Gina. Always so busy at the hospital but blissfully home all by herself that Friday afternoon and quickly absorbed in a pay-per-view movie. She wanted for nothing as she sprawled on the couch with a mug of tea in front of her and the remote control by her arm. Then – wouldn’t you know it – the lights flickered and went out.

Each of the short paragraphs was written by a different person but says essentially the same thing in a slightly changed style. Whether it is providing additional information or stating the facts in a more straightforward or in an indirect way, nuances in writing are generally what a writer’s voice is about.

Developing your own voice is one goal of all authors, and it is important because it makes you different from other writers. Your words are part of your personality and without your own imprint on them, will sound boring—shallow and lifeless. By adding your unique spin on what you write, readers will be more interested in what you have to say.

So just like in real life, your voice is who you are. You won’t want to sound like anyone else. If you are not one to use big words in your everyday speech, don’t feel that you must add them to your manuscripts (and remember that your reading audience likes the ease of reading somewhat effortlessly through a story.)

So just like in real life, your voice is who you are. You won’t want to sound like anyone else. If you are not one to use big words in your everyday speech, don’t feel that you must add them to your manuscripts (and remember that your reading audience likes the ease of reading somewhat effortlessly through a story.)

Write how you talk and be consistent. The more you write, the more your authentic voice will emerge and you won’t sound like anyone else. Probably the best way to develop your voice is to plow through creating your first draft without thinking much about the words you write, the sentence structure, or the way the words sound. Just write with abandon and get your ideas down.

After the first draft is complete, reread it and revise as necessary, keeping true to the way you want the manuscript to sound to your readers. The less you attempt to embellish your words, the more the voice will be your authentic self and readers will recognize you. Read your own words aloud and think about whether it sounds like you.

As you read stories and books going forward, pay close attention to the differences in writers’ styles, words, sentence structures, and ways of creating a story—their voice. By doing so you will develop a strong and authentic voice for your own writing.

In our next blog post, we will discuss your characters’ voice – equally important and fun to practice as you get to know your characters and present them to your readers.

Susan Ludwig, MEd has been an instructor with the Institute of Children’s Literature for almost twenty years. Susan’s writing credits include teacher resource guides, English language learner books, and classroom curriculum for elementary through high school students. A former magazine editor, she assesses students’ written essays as a scoring director for the ACT and SAT exam. When she is not writing or working, she is usually found playing with her grandsons or curled up with a good book.

To many, writing is revision, and most writers revise their manuscripts numerous times before they’ve shaped it into the best version that it can be.

We’re going to look at influential female authors of the past, those impacting the present, and whom the industry expects to make a big splash.

This week, we’re focusing on how we as writers can create strong female characters that others will look up to, instead of harmful stereotypes.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

1 Comment