1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

Basically every book I write is an adventure story or a mystery, and many are both. By definition, a mystery involves a puzzle with someone trying to solve the puzzle. For adults, most mystery stories involve crimes. In children’s books, the puzzle is sometimes a crime, but often not, especially for younger readers.

One interesting thing about mystery stories today is that often they are not overtly called mysteries. When I was young, kid novels often included the word “mystery” right in the title, because that was a huge draw for the reader (along with other signpost words like “secret,” or “clue”). But the puzzle aspect of the mystery novel is often mixed in with other genre today. For example, my Monster Hunter novels almost always have mystery plots: who doesn’t want the team investigating the Chupacabra sighting? Is there a human behind the sudden increase in Swamp Ape sightings? And who is sabotaging the movie about the Loveland Frog? Readers sign on for the monsters, but it’s the mystery that hooks them until the end of the story. And this attention-grabbing aspect of mysteries can work with even the youngest readers.

Mysteries are made up of several things: a puzzle to be solved, clues to give you the potential chance of solving the mystery before the end of the book, a main character who has a strong motivation to solve (or at least respond to) the mystery puzzle, and a resolution where we learn the answer. All of those things work together to create the story, and they all need to make sense. We need to believe this main character would definitely respond to the puzzle in this way. We need to believe that other characters are behaving in a logical manner as well (meaning you can’t have a character do nonsensical, strange things just because it’ll give you a chance to give a clue). Keep in mind that not all the clues should point to the real answer to the mystery. Some clues are distractions or red herrings. They are things that are also logically happening, but that might pull the main character and the reader off the trail (at least briefly). And the elements of a mystery can happen in books for every age of reader.

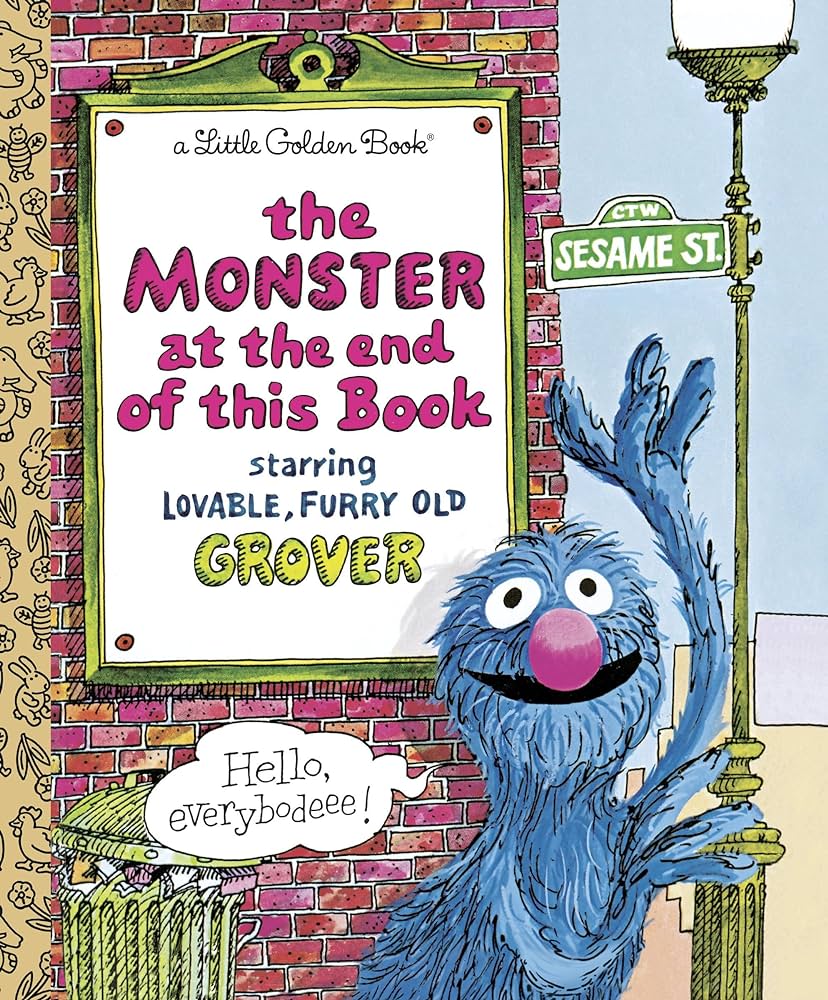

Let’s look at a popular picture book that most of us have read (or are familiar with) that is basically a mystery. The book is The Monster at the End of This Book. This mystery is one of the most interactive stories ever published for very young children, but it also contains the basic components of a mystery. Let’s look at how the book provides us a puzzle, at least one clue, a motivated main character acting on the puzzle, and a resolution.

In The Monster at the End of This Book, the actual detective is the reader. The reader mushes on to solve the puzzle despite Grover’s antics to prevent it. That’s another hint. Grover, who appears to be the main character, is actually the antagonist whose actions prevent the actual detective (the reader) from solving the puzzle by pressing on to the end of the book. Grover’s panicky action and his apparent belief that there will be a different monster at the end are red herrings thrown in to distract the detective.

So you can see that mystery stories can even work for children who are very young. This story is extremely simple and told with a very low word count, but it still contains the elements of a mystery. The twist of having the reader be the detective is different, but perfect for young readers.

As readers age up, mysteries become more complex. The number of clues increase with a mix of valid clues and red herrings. The person setting out to solve the mystery will usually be an actual character. There may or may not be an antagonist as that is not a required element of a mystery (though it is almost always there in mysteries for middle grade readers and older). As we saw in the book with Grover, the antagonist might not see himself as the “bad guy.” The best antagonists believe their actions are totally valid.

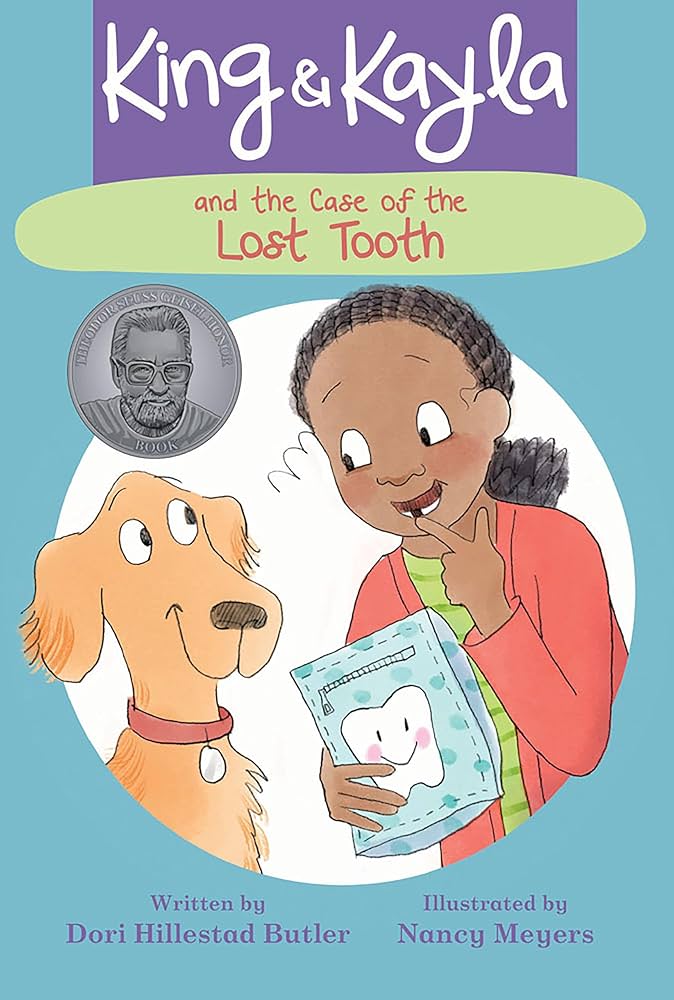

Clearly, the “mystery” here, like the one in the Grover book, is not a crime. In the beginning, we learn Kayla lost a tooth at school so she put the tooth in a fairy pillow (loaned to her from her classroom) and is looking forward to the tooth fairy trading the tooth for money. Unfortunately, she immediately discovers the tooth is missing from the tooth fairy pillow. Thus, the mystery puzzle: we clearly must learn what happened to the tooth. Thus we have a highly motivated “detective” in Kayla and a puzzle to be solved.

Now, what about clues? The first clue is that she showed the tooth to someone during the car ride home, so we rush to the car to look for the tooth. No tooth. We also have the clue that the person she showed the tooth to was Mason, so we go check out that clue. Mason says he doesn’t have the tooth, but they should make a list of what they know. Plus, King has discovered a clue: Kayla’s teeth smell like turkey sandwich. Mason’s hand smells like turkey sandwich too. So King searches Mason but doesn’t find the tooth.

Kayla wonders if the tooth fairy somehow took the took from the pillow. But the tooth fairy leaves her a note saying she did not. King searches the pillow again and notices it smells like turkey sandwich. He looks closer and finds a hole. He pulls out some stuffing. The tooth falls out. The mystery is solved.

Because this is a longer story, the clues are more complex and include red herrings like Mason smelling of turkey which makes King think Mason may be the culprit. Even this red herring actually hints at a true clue, the smell, which ultimately solves the mystery.

One important thing to keep in mind for both of these young reader mysteries is that the mystery would not be solved without the action of the “detective.” In the case of Grover’s story, the child reading/listening to the book must do the action of solving the mystery by turning pages. In the case of Kayla & King, King must track down clues and follow his nose to solve the mystery. The mystery needs to be solved by action on the part of the detective.

This doesn’t work as a mystery story because the actions of the main character don’t matter at all. If he had called his grandmother, then gone off to play with his action figures, his grandmother would still have showed up at the end. If he had run and asked his mom and she’d told him he worries too much and set him down to do his homework, his grandmother would still have shown up at the end. Nothing that “detective” did mattered, and that makes for an unsatisfying (and often difficult to sell) story.

So beware that trap as it catches many newer writers who are attempting a mystery story. In a mystery, as in any story, the behavior of the main character must matter for the ending to be satisfying. Keep that in mind and all of your stories, mysteries included, will be better and far more likely to sell.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

3 Comments