1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

Many people decide they must be picture book writers because:

2. They want to write short things, and/or

3. They assume picture books will be easier than a novel.

I heard a talk show host dismiss picture books as something “knocked out in an afternoon” and thus less impressive than writing a novel. And yet, some picture books take years to write because the demands of the art are quite challenging.

Now, if you happen to be a person whose name is known to millions because you’re an actor, singer, politician, athlete, or even novel writer, you may be able to publish a picture book that you actually did knock out in an afternoon.

But the rest of us have to actually meet the demands of the art. We have to be good, because that will be the only point upon which the publisher can sell the book. Being good at writing picture books means being able to do three things well: sound, story, and emotion. Let’s look at these one by one.

The audience for the vast majority of picture books are not going to read the book. They’re going to listen to it. Picture books are a communal experience beyond anything else in writing. There will be three artists in the presentation: the author, the illustrator, and the reader. Now, we can’t know what the skill level of the reader will be, so the picture book author must help out by making sure the book sings no matter who reads it out loud. You may be able to “perform” the book you’ve written well, but if you hand the manuscript over to someone else, does it still light up the room when it’s read aloud? A skilled writer will produce a book that supports the reader through the sound of the text.

But not writing in rhyme and meter doesn’t mean sound becomes unimportant. Sound will always be important in picture books. And surprisingly, so will meter. When writing a non-rhyming picture book, you loose yourself from the bounds of perfect meter, but picture book prose is over metrical. It sings; it just doesn’t rhyme. If you were to chart the stressed and unstressed syllables of prose picture books that have stood the test of time, you’re going to see patterns. Not the perfect patterns of rhyming picture books, but still, patterns that feel good in the mouth and sound good in the ear.

As writers, we need to be aware of the feel of the words in our picture books. The difference between a line that gives us interesting information and a line that gives us interesting information in a euphonic way is huge. For example, suppose my character looks into a huge box of junk at a yard sale and sees a wild collection of different items. In fact, he nearly falls into the box in his excitement of discovery. Imagine he sees sporting equipment, and old dolls and stray encyclopedias. How could I share that in a way that is euphonic? I could use near rhyme and assonance like this: “He found baseball bats and dolls of wax and dusty, musty books of facts.” That line uses both meter, assonance, and even a little perfect rhyme to make it interesting to read and interesting to hear. So we should tinker with every line in our picture book stories until we make them sing in the mouth of every reader.

Now, not every picture book tells a clear story. Some of the most popular are basically just character sketches (Olivia would be one example), but the picture book that editors will want to see from you will need to tell a story. The story might be almost any genre, such as an adventure––this is probably the most common because it lends itself so well to picture books.

A mystery––this is less common because picture books must stay interesting even when you know the ending so the journey to the ending must be super interesting.

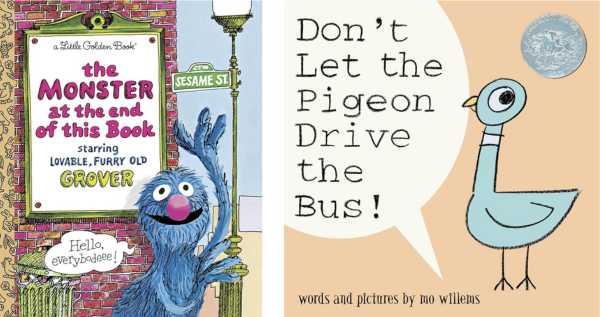

Examples: The Monster at the End of this Book, or Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus.

Many picture books have fantasy elements like talking animals or pretend monsters, but very realistic picture books happen as well.

A narrative arc will usually include plenty of action, but sometimes the action is really brought to the story by the illustrator more than by the author. In Guess How Much I Love You, a little hare and an older hare are having a competition, of sorts, about which loves the other most. The competition is mostly dialogue, so the illustrator brings in the action part of the storytelling by showing them on a kind of journey to bedtime. Though the action is more in the illustrations than the dialogue, an arc still exists. The reader is interested to see which character will “win” in this competition.

A check of your story arc can be made by asking yourself what each of the characters wants in the story and how they are in conflict. The story of the hares has each character trying to win a competition. So the conflict is obvious, as is the effort to overcome. In Where The Wild Things Are, the main character is looking for a place where it’s acceptable to be a wild thing and he sails away in search of such a place. He finds it, but then ultimately realizes it’s not enough and comes home. And when he gets home, he sees “wild things” can find love there as well. Remember: the character who “wins” in the story should be the character the young reader is rooting for. This is one place that Guess How Much I Love You falls down a little. The parent “wins” though the young reader rarely roots for parents to “win” over youngsters. But the book is aimed at the parent as much as the child.

This is another ball to juggle in your story choice. Your adult reader must like the book as much as the child or the book might not become a family favorite (I’ve heard of books “disappearing” even when the child loves it because the adult didn’t enjoy reading it).

Now, you’re generally not looking to write a picture book that makes you cry (though Polar Express can make me a little misty eyed when I read it), but you do want your picture book to generate some kind of emotion in the reader. Some books hope to give the child a feeling of emotional security (examples would be Guess How Much I Love You and Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site). Books designed to give emotional security often tend to be bedtime books and the pacing and tone reflect that. They’re meant to be read softly. They have distinct meter choices and soft word choices. Sending a child off to bed with that cozy feeling of emotional security just seems like a good match.

So study your picture book manuscript. Read it aloud. Have someone read it aloud to you. Have more than one person read it aloud to you. Note places where the manuscript is especially pleasant to hear. Keep those. And keep working on the rest until the book sings.

Once you know those things, you’ll have three very important balls in the air as a picture book juggler and be on your way to picture book writing success!

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

4 Comments