5 Ways Writers Can Prep for 2025 Goal Setting

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

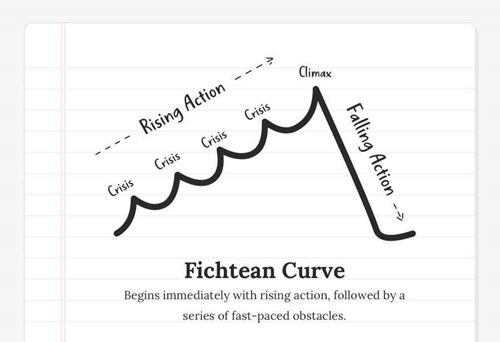

For novels, chapter books, short stories, and the majority of picture books, plot is an essential tool for successfully writing a children’s book—or any book. Plot is the structure that brings motivation, action, setting, dialogue, characterization, theme, and conflict together in a way that makes sense, drives the story, and results in a satisfying and engaging read. For newer writers, this can make plot daunting, but the core to understanding plot is purpose.

In a well-plotted story, every moment has a purpose. For any given sentence or character or bit of dialogue or action, a writer needs to know the purpose of the inclusion of that element. The purpose could be directly tied to plot, such as needing to justify moving a character from one location to another where an important event will take place. Or the purpose could be more loosely tied to plot, such as revealing the insecurities of a character through dialogue so that readers will better understand and accept the character’s choices throughout the story. But whether the reason is directly tied to plot or not, the choice cannot be arbitrary.

But even with an extremely well-read author, this kind of seat-of-your-pants writing always results in extraneous bits that felt good at the time but didn’t ultimately serve any purpose. These parts can’t be justified or explained as part of the story whole. When that happens, they need to come out of the piece during the revision step. Sometimes during successive revision steps more and more such unjustified bits reveal themselves and require cutting. The result is a story that is tighter, better paced, and more engaging and satisfying for the reader.

At the beginning of most plot creation is an idea. The sort of idea you can begin the story with is limited only by the writers imagination and experience. You may begin with a character who pops into your head and seems to insist on being written about. When I wrote early readers for a literacy program, I knew I wanted books with dragons as I’d always loved dragons but hadn’t done any stories with them. So my first step was knowing I wanted to do dragon stories.

When I thought about dragon stories, I brainstormed conventions of dragon stories. In other words, I thought about the most common things we associate with dragons. Dragons love gold. Dragons carry off princesses. Dragons are huge and terrifying. Dragons live in caves with their treasures. And dragons are hunted by brave knights.

When I thought about brave knights, I immediately landed on the idea of a family of dragon slayers who were just ridiculously good at slaying dragons for generation after generation. All the way down to Alfie, who didn’t want to slay dragons at all. I imagined a boy who didn’t fit into his family’s “story,” the one they had always told about themselves. Alfie didn’t fit no matter how hard they tried to make him fit. So that was the basic idea that began the story plot journey. How does a boy find his own way when everyone around him thinks he has this destiny?

For my next dragon story, I returned to my list of dragon conventions and I thought about how dragons carry away princesses. One of my favorite picture books, The Paper Bag Princess, turned that convention on its ear, and I wanted to do something else inspired by the dragons and princess premise. But this little scrap of dialogue popped into my head: “You, my dear, are no princess.” And from there, I asked myself, what if someone was told they should be safe from dragons because dragons only carry off princesses? And what if that was wrong? And it was from that basic idea that I came up with the plot for The Dragon of Woolie, where the dragon carries off a very non-princessy shepherd boy.

Neither of these ideas was instantly a plot. They were simply the seed from which a plot grew. I needed to water the seed by seeking out what sort of plot elements fit this seed.

Once you have a seed, you need to begin looking at the other plot elements that are necessary to make a good story, and sorting out what these things look like in this story.

So that’s my seed. To make it sprout, I need to begin examining the other plot elements to discover what I need to make this seed into a story. The first thing I want to find is conflict. Conflict drives plot forward.

In my premise, I have the basic conflict of the characters knowing this horrific thing, but not being able to convince anyone else because they aren’t believed. That conflict might not be resolved, but then again, it might. It could also lead to inner conflicts about feeling inadequate to do anything about the problem, being afraid, being overly self-focused. Any of these inner conflicts could increase the difficulty of dealing with the story problem (monsters). And the other obvious external conflict is that there are monsters and monsters are a force of conflict all by themselves.

Once I have my conflict, I can begin staffing this story. What kind of characters work best in this story? My elderly character can be curmudgeonly or friendly. My child could be brave or terrified. The characters can be impulsive or prone to thinking things through carefully. Every choice I make in these two essential characters will affect the events that occur in the story. Every time I make a choice, it means certain other choices are no longer available but new choices have popped up. Because choosing results in eliminating some options, I need to choose wisely to send my characters on an adventure that will affect the situation. The situation (monsters are real) may be terrifying and even hopeless at first glance, but if I make the right choices as an author, these two people can ultimately do something about the problem.

Choosing the conflict and the characters are the most important elements in making the story seed sprout, but they aren’t the only things you need.

There is one important element that will weave through the story and affects the plot, usually in subtle ways. This is theme.

Sometimes I brainstorm a list of possible themes inspired by my core idea, conflict, and characters, then choose from the list. But sometimes, theme takes a little longer to find.

A theme doesn’t always reveal itself until you begin writing. That’s perfectly normal. But you really should be able to say (at some point) what your story is revealing thematically. You might be saying something about courage, or about family, or about friendship. Whatever you choose will be the theme that is right for you.

Without a theme, a story often feels shallow and doesn’t linger in the reader’s memory. Your theme doesn’t need to be stated outright and certainly shouldn’t be stated in a “the moral of this story is” kind of way, but it should affect you and the choices you make as you tell this tale.

After you have your story idea seed, and you’ve found your cast of characters and your core truths and conflicts, you’ll be ready to begin writing or outlining (depending on your writing style). I like to preplan stories by telling myself the story and writing down the broad strokes as a kind of lengthy synopsis. This lets me see if I have done enough pre-thinking to know how the story will go. Then I inflate this framework when I actually begin writing the scenes and dialogue and action that I planned during the synopsis/outline step.

As I’m outlining, I am thinking about the fact that my story needs a clear beginning, middle, and end. In the beginning, I’ll set the stage and setting, meet the characters in action, and drop the story idea on their heads. This will get everything going.

In the middle, I’m working the plot problem. My boy and neighbor team will do things to solve the problem. The choices they make and the actions they undertake must make sense to who they are and the situation they are in. I may make them reluctant to face monsters (I know I would be). Thus, the neighbor calls the police, but the police are not helpful. The boy and neighbor are going to have to solve this on their own. Choices shut the door on some options, but other options always pop up.

Equally, I can’t have the elderly neighbor’s family swoop in and dump the neighbor into care, based on the belief that the old person has lost it. I can use the threat of these things happening to up the tension, but if I actually pull the trigger on these possible consequences, I must also come up with believable workarounds to them. If I discover I’ve written myself into a wall (and it can happen) I need to go back to the point where the plot was working and I had lots of choices and move in a different direction.

Believability is key. Readers have to believe that in these circumstances, that these characters would act and react in these ways. And I must keep things moving so that the reader is swept along by my pacing, and maybe doesn’t overly examine things like why are there monsters here? Sometimes “there are monsters” doesn’t ever get explained because the story is about “what if there are monsters” and what happens in that situation.

If I’ve planned my story well, the ending will also make sense. It will be the reasonable ending that comes from what I’ve done prior to that moment. It won’t happen because the elderly neighbor suddenly remembers he used to be Rambo. It won’t happen because the impulsive child suddenly remembers a paper he read on opening portals between dimensions. It will happen as the logical actions of these people just as every other thing in the story did. But this time, the characters will find success (or at least resolution) and the story will conclude. Maybe they don’t overcome the monsters. Maybe they only overcome the disbelief of those around them and no longer have to fight alone.

The ending should not have been obvious from the beginning. A story that runs in a very straight line isn’t a particularly interesting one. If I tell you the story of how I painted my first bird in watercolor and the end result is that it was imperfect but I liked it, you’re not going to be overly surprised (or interested). If I tell you the story of how I painted my first bird in watercolor and it won an award for thousands of dollars and launched my brilliant career, you might be surprised, but you probably will not find that believable. But if I tell you the story of how I painted my first bird and my cat was so taken by the process that he ate the picture when I walked to the kitchen to rinse out my brush—that ending would be funny and unexpected and wouldn’t stretch believability too far. That would be an ending worthy of a story.

We’re going to look more at plot throughout this month and some of the nuts and bolts of how plot works, as well as some tips for creating them well. I hope you’ll come along on the journey. For me, that’s the happy ending I want most.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

Before we roll on to the new writing year, let’s harness our optimism for the blank slate before us and prepare for our 2025 Goal Setting just for writers.

Writers can be thin-skinned when it comes to getting feedback on their work. Let’s look at 4 ways to positively deal with constructive criticism!

Rejection is part of the territory when it comes to being a writer. Today we offer reflection for writers to help redirect your efforts after a rejection.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

9 Comments