1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

A short story is exactly what it sounds like, a story of not very many words. Editors determine how many, and they decide based on how much space they have available in their publications. Even online magazines ask for submissions based on word count.

The best length to aim for is, in my opinion, 1,000 to 7,500 words. The sweet spot is around 3,500. One of my favorite short stories, A Rose for Emily by William Faulkner, is 3,715 words.

Novelettes run 10 to 20K words or 40 to 80 pages. My favorite of these, Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut by Stephen King, is 11,400 words. Novellas are 20 to 40K words and 80 to 160 pages. I have two favorites here: Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote, 26,433 words, and Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption by Stephen King, 38K words.

Stories shorter than 1,000 words are flash fiction. Micro fiction runs 350 to 1,000 words. The following 6-word story is attributed to Ernest Hemingway: “For sale: Baby shoes. Never worn.”

Playwright Anton Chekhov is considered the father of the modern short story. Edgar Allen Poe preferred short stories over longer forms of fiction because they can be read in one sitting.

Structure is order. In fiction, it’s arranging the most important elements of your story—setting, plot, conflict, and theme—in the best possible way for the story to be read. That’s why you don’t start with the end unless the story is a flashback.

Some genres have signature structures:

• Mystery relies on plot.

• Romance is driven by characters and conflict.

• Science fiction and fantasy offer settings that are out of this world.

Where you place the most important element of your story depends on the length. If you’re writing 7,500 words you have the pages to build suspense and establish setting and characters. The shorter the story, the closer to the beginning you should plant your most important element.

The first tool you have to accomplish this is the story arc—the circle of the flashback story. Freytag’s pyramid, named for Gustav Freytag, a 19th century German novelist and playwright, is another type of arc. Here’s what it looks like:

Look familiar? Yep, it’s the same 3-act structure as the nonfiction pyramid, only right side up. A bit dated, but still a good model to follow for shorter stories: exposition, climax, denouement. Better known these days as story problem, complication, resolution. Or:

For a 1,000-word story, which is 4 pages, you have about 1-1/2 pages for each act. For a 1,500-word story, which is 6 pages, you have 2 pages. For a 2,000-word story, which is 8 pages, you have about 2-1/2 pages. A 7,500-word story is 30 pages.

Those dividers are a rule of thumb. Divvy up words to suit the most important elements of your story, keeping in mind that the ending will likely require fewer words than the problem and the complication.

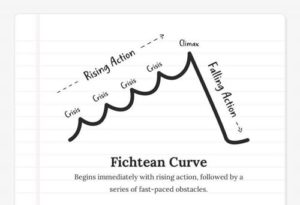

For a story longer than 5,000 words, or possibly one from 3,500 to 5,000, you can expand Freytag’s 3 acts to 5. But there’s a better 3-act structure for longer stories. The Fichtean Curve. Take a look:

There are several variations of this one. I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a new one next week.

Four climax points are better suited to a novel, but there’s stuff here to consider for a 30-plus page story, a novelette, or a novella: a “big twist” at the midway point, second thoughts, disaster, crisis.

Both sides of Freytag’s pyramid are nearly straight up. The ascending side of the Fichtean pyramid is more like a ramp, and the descending side isn’t as steep. Both shapes are indicators of pace. You need a lot of momentum to scale Freytag, but you can sort of take your time on the Fichtean ramp. Both shapes also indicate the page length.

In fiction, I use the 5 W’s to layout the bones of my story. This is the breakdown I use:

The way I fill in my W’s varies depending on the story, but that gives you the idea. Use the 5 W’s to keep the most important stuff in front of you—your eye on the ball so you don’t drop it.

Use topic sentences to sketch out your scenes. I want this to happen here, that to happen there, that kind of thing.

A last caveat. Be judicious about scenes breaks. In a between 1,000 and 3,000-words I don’t think you should have any breaks at all. Between 3,500 and 6,000 words, no more than three.

Other tools to help with structure: paragraphs, scenes, and point of view. We’ll discuss those and a couple more pyramids next time when we talk about novel structure. Start thinking big!

Lynne Smith, aka Lynn Michaels, is the author of two novellas and sixteen novels, three of which were nominated for the Romance Writers of America’s RITA award, the Oscar of romance writing. She won two awards from Romantic Times Magazine, for best romantic suspense and best contemporary romance. Her only complaint about writing is that it really cuts into her reading time. She lives in Missouri with her husband, two sons, three grandsons, and one granddaughter, born on Lynne’s birthday. Lynne is also an IFW instructor. She teaches “Breaking into Print” and “Shape, Write and Sell Your Novel.”

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

4 Comments