1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

We teach our students how to write and get published!

View our Course Catalog >

The covenant is the pact writers make with readers, the promise to deliver a riveting story with unforgettable characters and an ingeniously clever plot. The author also promises to tell the story in a smooth, logical, and easy to follow way. That’s why starting the story in the right place is especially important in a novel.

Readers don’t notice structure, yet we’ve all read stories or novels that were either impossible to get into or ridiculously hard. That can happen if the author starts in the wrong place. If readers can’t get their feet under them in your story, you’re sunk.

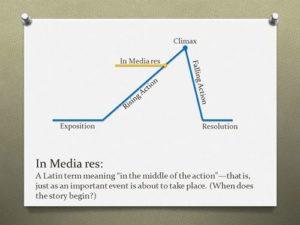

Structure, specifically story arcs, can help you determine the best place to begin the story. Let’s look at two more pyramids, a variation of the Fichtean curve and in media res.

That’s Latin for “in the middle of things”, and it was the first story arc I learned in creative writing classes. In media res is often described as beginning a story with your character up a tree. I did that, literally, in Captain Rakehell, a Regency romp I wrote for Fawcett; I opened the story with my heroine up a tree. It wasn’t an inside joke aimed at other writers; it really was the best place to start.

In the middle of things occurs after the inciting incident, the event that gets the story rolling has happened. In Captain Rakehell, the inciting incident is Lady Amanda Gilbertson’s betrothal by her father the earl to a man she despises, Lord Lesley Earnshaw, newly returned from the Napoleonic Wars. She climbs the tree in her satin gown and dancing slippers to avoid meeting Earnshaw at their betrothal ball.

Here’s what in media res looks like:

Captain Rakehell begins on the heels of the betrothal. On the rising side of the pyramid, that’s just a bit above the Exposition line. Short Regency romances clock in at 40 to 50K so the linear plot—boy meets girl, loses girl, wins girl back—is a good fit for in media res.

But not so much for the first volume of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring, which begins many years after Bilbo Baggins finds the One Ring in the caves beneath the Misty Mountains. That occurs in The Hobbit, the prequel novel to TLOTR. The inciting incident of Fellowship is Gandalf realizing that Bilbo has the One Ring.

On the graphic, The Hobbit serves as the Exposition. The opening of Fellowship takes place at just about where in media res is indicated. That’s pretty close to the climax, and there’s a lot of story between Bilbo giving Frodo the ring at his birthday party, the formation and dissolution of the Fellowship and Frodo and Sam heading off to Mordor on their own.

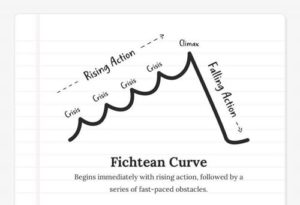

Here’s a structure that’s a much better fit for the many adventures Frodo and Sam have along the way, the second Fichtean curve.

The crisis points noted on the rising side of the pyramid look like waves on the surface of the ocean, rolling in and out until they crash on the beach at high tide, the climax of the story. In Fellowship, the first crisis is Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin encountering the Black Riders on the road to Bree. The second crisis is escaping the Riders at the inn in Bree, where they’ve met Aragorn.

The waves are divided into scenes and chapters. Just like a wave, each builds to a breaking point, falls, then climbs again to the next one. A chapter arc looks like this: rise, break, fall—problem, complication, resolution. The 3-act structure of Freytag’s pyramid.

A wave retreats to gather energy for another run at the beach. You should have your characters doing the same thing during lulls between crises—regrouping, evaluating, planning what to do next.

Readers catch their breath in lulls, and the author, usually in dialogue, recaps what has happened so far in the story so readers can keep up, not in every lull, but every few chapters or so.

The Fichtean wave works for fantasy novels, mysteries, thrillers, any kind of novel that has a lot of action. Overlay in media res with the Fichtean wave and there’s the structure I’ve followed for most of my novels. I didn’t figure that out until I sat down to write these posts.

Yes, you can mix and match. Nothing about writing is cut in stone. The only rule is, does it work? Does it make the story stronger and better? There are other story arcs you can try, as well. The 7-point story structure sort of looks like a graphic of the Loch Ness Monster.

The best way to learn structure, and to learn how to write, is to read. I read every day for at least a couple of hours because it’s my most favorite thing in the world to do. Your brain is a sponge. You absorb all kinds of things beyond the story you’re reading—you soak up the way the author structures sentences, constructs scenes, ends a chapter and begins the next one. You aren’t aware that you’re learning all those things, but you are, and trust me, it will be there when you need it.

An instance that brought that home to me was my agent’s suggestion that I try my hand at writing Regencies. I love Regencies, I’d read hundreds of them, which my agent knew, but I claimed I didn’t know enough about the genre or the period. “Phooey,” she replied. “You know more than you think you do, so dub your mummer (a Regency slang phrase that means shut up) and give it a go.”

I did, and by golly, she was right. Everything I needed to know to write a Regency was all in my head and just rolled off my fingertips.

The result was Captain Rakehell. That can happen to you, too!

Lynne Smith, aka Lynn Michaels, is the author of two novellas and sixteen novels, three of which were nominated for the Romance Writers of America’s RITA award, the Oscar of romance writing. She won two awards from Romantic Times Magazine, for best romantic suspense and best contemporary romance. Her only complaint about writing is that it really cuts into her reading time. She lives in Missouri with her husband, two sons, three grandsons, and one granddaughter, born on Lynne’s birthday. Lynne is also an IFW instructor. She teaches “Breaking into Print” and “Shape, Write and Sell Your Novel.”

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

2 Comments