1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

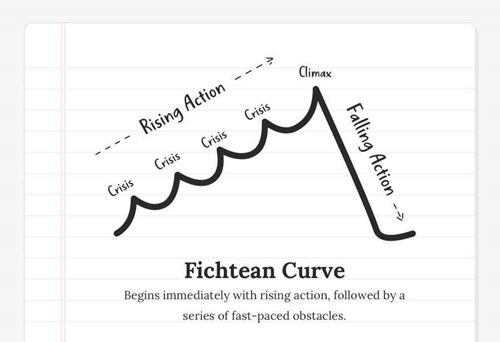

Long ago, when I first realized that my fiction would sell worlds better if I had any idea how to go about telling a good story, I started reading about plot. Plot seemed like a rather mysterious thing that required analyzing and piecing together like one of those horribly complicated puzzles where both sides are blank and every piece is a different shape.

Honestly, I actually sold my short story years and years before I ever understood that plot arc thing. For one, I normally built a plot by taking a perfectly nice character and tossing him or her into a fantastically dreadful situation. She’d have a terrible fight with her absolute best friend. He’d go looking for his lost puppy and fall off a cliff. At the very least, the character would be saddled with the hardest possible school assignment while grouped with the worst project partners in the world. In other words, things would get bad. How did a drawing of things looking up and up and up relate to a plot where things got bad, then worse and worse and worse? Wasn’t that arc thingy upside down?

Then somewhere along the way, the plot arc began to creep into my rather slow wits. You can look at the arc image in a lot of different ways. So let’s look at a few of the ways I’ve imagined the arc.

Imagine that funky arc as a mountain. It may have bumps along the way since few mountains aren’t quite as straight and pointy as the ones we drew in elementary school. The mountain is the continual climb the main character must make as he tries to solve the plot problem, a climb that gets harder and steeper as the character goes along.

A good plot always has the potential for failure for the main character). Once he has succeeded, he comes down the other side where life is easier. Maybe there’s a ski lift to ride on that side.

Anyway, after the moment of crisis, the climax, we tie up any loose ends that absolutely must be settled. This post-success settling down is your dénouement.

But the steady climbing of the action is only one way to look at the plot arc.

What could be more tense than a single pounding heartbeat? We’ve all seen the hospital room scenes were the heartbeats are registering as sharp jumps on a screen. Those heart monitors are tense to watch and tension is another way to look at plot arc.

Plots need tension or we’re not going to care whether the main character keeps up his efforts or if he succeeds at all. Tension is provided by the sense that something rather important is at stake. Now, it might not seem all that important to the reader, but it needs to be clearly very important to the main character. So tension is connected to the importance of the plot to the main character and our connection emotionally to that character. The character cares. We care about the character. Therefore we care about the plot.

The thing about tension is that it’s a bit like rubber. It stretches, but it also breaks. Stretching tension gives the story more energy (just as stretching a rubber band will give it the potential energy to snap you painfully in the hand). But when tension is broken, it’s hard to get it going again. Things that will break tension are clunky writing, viewpoint switches, flashbacks, and easy answers. A reader will let you delay the story a bit while we slowly walk through the haunted house with your heart pounding in your chest, but if you just switch to a long internal monologue about how the character should have done his homework, you will poke a hole right in your tension and let it leak away. So be careful with how much you stretch it.

Sometimes it’s good to look at an analogy in a totally new way, so go ahead and turn that arc completely over. I like to look at the plot arc upside down sometimes because you can also see it as the slow decline from “normal” to “catastrophic” where the plot problem makes the main character’s life worse and worse and worse. This is often the case in comic adventure or comic horror where the plot grows ridiculously worse and worse. The main character is trying to prove his mature responsibility so he offers to look after his teacher’s beautiful white show dog. And the dog runs away. The main character chases after it, accidentally chasing the dog right through the path of someone painting a wall bright green with a power sprayer. Now the main character is chasing a green dog. He chases the green dog right into a bank where a robbery is taking place. Do you see? The poor kid is running downhill fast in the plot arc as things get catastrophically worse and worse and worse. Everything he tries just makes it more horrible, until it actually hits bottom where it’s all doomed to end–only it doesn’t. The kid finally figures it out. He makes the choice that changes everything. And we just crawl out of the pit with our dénouement.

So those are some new ways to look at that weird plot drawing that didn’t make sense to me for the longest time. I hope it helps you see it in a new way.

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

©2025 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

3 Comments