- Date: January 2, 2020

- Author: Jan Fields

- Category: Writing for Children Blog

- Tags: Middle Grade, novels, Writing for Children and Teens

We teach our students how to write and get published!

View our Course Catalog >

Writing Contemporary Realistic Fiction

As we study our market guides for the new year, one of the things we’ll see in each listing will be the genre the publisher accepts.

One category often found is “realistic fiction.” It is also sometimes called “contemporary fiction” or even “contemporary realistic fiction.” All of these mean the same thing. Realistic books are books in which the plot could happen, all the elements are within the realm of reality and not implausible. And books found under the “realistic fiction” heading are generally set within the last decade.

When a book is set twenty years or more in the past, it is considered historical fiction. The middle distance between a decade and twenty years is a bit of a limbo and genre is determined by things like tone and situation.

When a book is set twenty years or more in the past, it is considered historical fiction. The middle distance between a decade and twenty years is a bit of a limbo and genre is determined by things like tone and situation.

The designation “realistic” doesn’t mean every other genre is unrealistic. Most historical fiction strives for realism and accuracy and authors spend considerable time researching to ensure a realistic portrayal of the time, the people, the setting, and the situation. And some mystery or thriller writers are equally scrupulous about realism and research. But the novel will still be classified as a different genre from realistic fiction, not because of a lack of realism but because of the addition of something else.

The addition in mysteries is the puzzle plot and the addition in thrillers is the high suspense and tension. The addition in action-adventure is (rather obviously) the plot that rushes from one bit of excitement and demanding action sequence to the next. Realistic fiction must engage the reader and keep them engaged without the boost of those things.

Realistic Fiction and Characters

One of the strongly determining factors of realistic fiction is multi-dimensional, compelling characters. In fact, realistic fiction is usually character driven, so your characters must be very strong in order to keep the story engaging. Characters should not simply be a vehicle for the writer to teach young people today how to behave.

Sadly, what many submissions publishers receive as realistic fiction are actually thinly veiled lectures intended to teach young people. For middle grade, the lessons often include gratitude (especially toward parents) and being less self-focused. Characters in failed realistic fiction for this grade level are often selfish and whiny, because the point of the story is to teach children not to be selfish and whiny. In failed teen stories, the characters often make poor choices in terms of drinking or drugs. The “drunk driving will ruin your life” story is especially common in unsuccessful submissions. Realistic fiction for children and teens is held to the same standard as realistic fiction for adults. Adults aren’t looking to be nagged through fiction and neither are young people. No one likes to be lectured!

Fiction’s job is to engage. Good fiction also leaves you thinking, but it doesn’t tell you what to think. If the reader learns something, it will be because that reader connects with the characters, and we rarely connect with a character who is a whiny, selfish monster. Basically, if you have little respect for the age group you’re writing about, you’re unlikely to do it well. So if you have an interest in realistic fiction, target the reader age that you admire and respect.

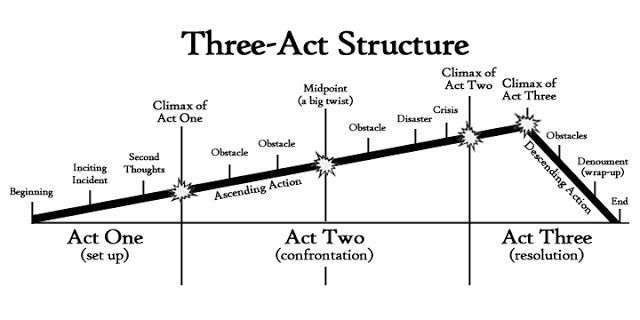

Realistic Fiction and Plot

Realistic fiction is usually character driven, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t need a plot. A plot is simply the logical sequence of events in a story that build toward the end through tension, and through challenge. Plot is built through pressure that compels the main character to act. If there is no pressure from the character’s needs and situation, then you’re unlikely to have a compelling story.

Many people attempting to write realistic fiction for the first time will simply recount an experience that happened in their own young life or to their child. The story has meaning and importance to the writer because it is personal, but it lacks engagement for the reader because there is no plot. It’s simply a recounting, not a story.

A story with plot works toward something. The character is compelled to act by circumstance and will continue acting until the pressure from the circumstance is resolved. For example, a child who finds himself in a class with a teacher he feels hates him might find the situation intolerable. He may feel compelled to act to change this painful situation. He would have a number of possible choices: he could try to remove the teacher, or try to get the teacher to like him, or try to get his parents to change his classroom. All of these would be possible choices in response to the pressure the child feels. All might be difficult to accomplish, but only one should work well with the character and situation you’ve developed.

A story with plot works toward something. The character is compelled to act by circumstance and will continue acting until the pressure from the circumstance is resolved. For example, a child who finds himself in a class with a teacher he feels hates him might find the situation intolerable. He may feel compelled to act to change this painful situation. He would have a number of possible choices: he could try to remove the teacher, or try to get the teacher to like him, or try to get his parents to change his classroom. All of these would be possible choices in response to the pressure the child feels. All might be difficult to accomplish, but only one should work well with the character and situation you’ve developed.

For instance, the child may be in a class with his two best friends so he definitely doesn’t want to ask for a change of classroom. And the child may think the teacher could never like him (the reason for this should be built into the characters and situation). Given those two parameters, the child might try to get the teacher out. Maybe he’d try putting a rubber snake in her chair or a frog in her desk to get her to leave. When that doesn’t work, maybe he even might tell a lie about the teacher that leads to repercussions he didn’t expect and now must decide how to resolve. All of the choices the character makes should grow out of the kind of person he is and thus will make the story feel realistic. In this plot, the resolution might not remove the teacher, but give the teacher and the child a new respect or appreciation for one another. Or maybe it will remove the teacher, but the child finds that doesn’t make him happy as he is racked with guilt, so he has to do something to resolve his feelings about what he has done.

The story will end when the pressures the story creates are resolved in some way––but the resolution must make sense. The resolution must also come about because of the character’s actions (a plot where the ending would have happened regardless of what the child does robs the reader of a sense of satisfaction at the end.)

Realistic Fiction and Dialogue

Because realistic fiction is contemporary, some writers strive to be very current in the dialogue in terms of slang or pop culture references. This can sometimes create issues for selling the book because current slang is so fleeting. What is current when you write the book may not be current when you’re revising the book and be extremely “out” by the time the book is in print. So trying to be very current in slang use is usually a bad idea.

Still, you want your dialogue to sound and feel realistic. This is usually conveyed through casual grammatical constructions and a sense of energy in the speech (for young characters) and/or attitude (for older characters). And all of that grows out of the characterization.

Still, you want your dialogue to sound and feel realistic. This is usually conveyed through casual grammatical constructions and a sense of energy in the speech (for young characters) and/or attitude (for older characters). And all of that grows out of the characterization.

You’re creating people who need to feel well-rounded and real. If you do a good job of creating these people in your head, then chances are good that they’ll sound realistic when you have them speak. Beware, however, of gimmicky ways to “explain” the use of old pop culture references or slang. It has become almost cliché in middle grade and teen novels that the main character just happens to love the music and movies that were current when the author was young.

One way that authors create characters who aren’t tied to a specific fleeting moment in pop culture time is to make up likely sounding bands that character loves and movies the character goes to. Realistic fiction is a facsimile of reality, so it’s all right to come up with your own inventions for the trendiest brands or media the character loves. And tie the story to those things only when you really need to do so. A character who is in crisis may not spend much time thinking about movies at all (or maybe thinks about them all the time, it really depends on how you’ve created the character). Whatever choices you make, be sure they’re a product of the people you’re creating and the plot you’ve set in motion.

Last bits

There are a few fiddly bits that you have to think about when writing realistic fiction. One is to choose whether to write in first person or third person. In other words, will the main character be telling his own story (which would be first person, meaning the main character is referred to as “I” in the narrative) or is it a story about him but following him closely (in which case it would be third person and the main character will be referred to as “he” in the narrative). First person narratives are common in teen realistic fiction and relatively common in middle grade realistic fiction, but don’t be afraid to use third person if that’s what feels right for the story. Some publishers have a preference of one over another but you should write what works for you and for your story.

Another thing to think about is setting. Realistic fiction tends to have plenty of descriptive detail of setting, so it might be a good idea to choose a setting that you are comfortable with. Readers can quickly tell when you’re making a hash of the setting. So if you have no personal familiarity with urban settings, it might be better not to try to write an edgy, urban novel unless you’re planning to go and immerse yourself in that setting during the writing. Research will carry you a long way, but some things (like the attitudes of the people) are best crafted from real experience.

Realistic fiction can be every bit as exciting and engaging as any other genre. It has its own challenges, but you may find it’s the sweet spot for your interests, experience, and writing skills. As with any genre, the more you read recent realistic novels, the better you’ll understand how this genre works.

As you read recent realistic novels, ask yourself if you’re enjoying the books. Often that’s a great sign of whether the genre might be right for you. If you don’t like reading realistic fiction, you may not enjoy writing it, and you may not do it well enough for publication. So take a trip to the library or bookstore and see what recent publications you can find.

This might just be the perfect path for you in the new year. Good luck!

Let us help you find the perfect genre for you in one of our Signature Writing Courses! Get started today and take our assessment!

Related Links

With over 100 books in publication, Jan Fields writes both chapter books for children and mystery novels for adults. She’s also known for a variety of experiences teaching writing, from one session SCBWI events to lengthier Highlights Foundation workshops to these blog posts for the Institute of Children’s Literature. As a former ICL instructor, Jan enjoys equipping writers for success in whatever way she can.

Become a better writer today

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1000 N. West Street #1200, Wilmington, DE 19801

© 2024 Direct Learning Systems, Inc. All rights reserved.

1 Comment